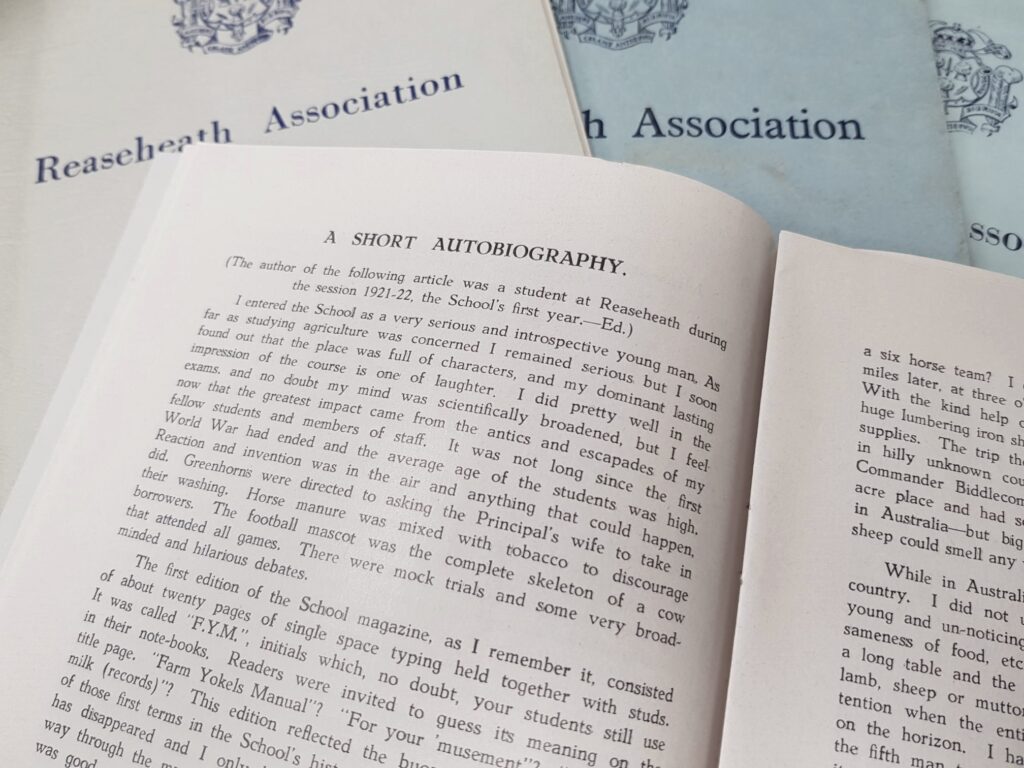

Written by Mr G A Plowright (student at Reaseheath during 1921 – 22) for inclusion in the Reaseheath Association Magazine in 1958

I entered the School as a very serious and introspective young man. As far as studying agriculture was concerned, I remained serious but I soon found out that the place was full of characters, and my dominant last impressions of the course is one of laughter. I did pretty well in the exams, and no doubt my mind was scientifically broadened, but I feel now that the greatest impact came from the antics and escapades of my fellow students and members of staff. It was not long since the first World War had ended, and the average age of the students was high. Reaction and invention were in the air and anything that could happen, did. Greenhorns were directed to asking the Principal’s wife to take in their washing. Horse manure was mixed with tobacco to discourage borrowers. The football mascot was the complete skeleton of a cow that attended all games. There were mock trials and some very broad minded and hilarious debates.

The first edition of the School magazine, as I remember it, consisted of about twenty pages of single space typing held together with studs. It was called “F.Y.M.”, initials which, no doubt, your students still use in their notebooks. Readers were invited to guess its meaning on the title page. “Farm Yokels Manual”? “For your ‘musement”? “Fluke your milk (records)”? This edition reflected the buoyancy of the atmosphere of those first terms in the School’s history. I regret to say that my copy has disappeared, and I only have memories of living and laughing my way through the mysteries of botany, zoology, and organic chemistry. It was good medicine for an over-serious introspective young man.

The certificate and reference obtained from the School made it easy to obtain an assisted passage to Australia and a farming career in a corner (Victoria) of that vast continent. I was there five years. I would like nothing better than to be able to tell you of application of the so recently acquired knowledge, of determined control of Bacterium acidi lacticus, of fostering the nodules that turn nitrites into nitrates (or is it the other way round?) of startling but praiseworthy results of breeding according to Mendelian laws, etc. but it just did not work out that way. Maybe I had, by that time, retired again into my introspective shell.

My first job was on an irrigation farm and my earliest memory is of fishing letters from home out of the canals – the mail man flung them over the fence if there was no one to meet him at the roadside and the letters floated down to the farm. Other memories of that farm – the foundation pillars of the home all stood in cans of kerosene; cows, after feeding heavily on alfalfa, got ravenous for water, became bloated and had to be stabbed just in front of the hip bone to let the (marsh?) gas out; – a mouse was found by the farmer in the cream one morning… but really that incident was too disgusting.

When I grew tired of a job I just quit and had a holiday in Melbourne. Then to a labour bureau for the next adventure. Could I drive a six-horse team? I certainly could. Thirty-six hours and three hundred miles later, at three o’clock in the morning I was introduced to my team. With the kind help of the other teamsters I got harnessed, hitched to a huge lumbering iron shod wagon and was on the road to Geelong to pick up supplies. The trip there and back took two days, and I was on my own in hilly unknown country; it was quite an education. My boss was a Commander Biddlecomb whom I never saw. He ran a sixty-thousand-acre place and had some forty thousand sheep – small as those things go in Australia – but big to me; and I don’t believe a hundred thousand sheep could smell any worse!

While in Australia I was sometimes told it was a young man’s country. I did not understand then, as I do now, that you had to be young and un-noticing to stand the heat and long droughts, the flies, the sameness of food, etc. At the Commander’s place thirty of us dined at a long table and the foreman always asked what we would have – “ram, lamb, sheep or mutton?” Eight weeks of drought was drawn to my attention when the entire station climbed a hill to observe a small cloud on the horizon. I had indeed noticed the shortage of water since I was the fifth man to wash in the same panful and had the duty of delivering it to a favoured fruit tree when I had finished.

Heat and water problems follow you everywhere upcountry in Australia. When I was a very new “new chum” I once asked a farmer if I could have a bath, but the padlock on the tap of his cistern did not get unlocked – he said, “Only dirty people need baths”, and I could not own to being that dirty. This was at a small dairy farm run by a very dainty couple. We changed for dinner every night, sat amid expensive furnishing and were very polite – we never acknowledged the skim milk but always said “Will you pass the cream”?

Oddly enough, the very next farmer I worked for sickened me with cream. At breakfast the first morning the three men I sat with each plunked seven or eight dessert spoonfuls of thick cream on their porridge and pushed the still half-full bowl over to me. I wonder if they noticed that I used only milk the next morning and that it was quite a while before I could handle my cream?

I had many adventures with snakes and some hair-raising experiences with whirlwinds. I heard about rabbit country and found that the man who told me the rabbits were so thick in his part of the world that he had to kick them out of the way to set the traps was only exaggerating the tiniest bit.

My last job in Australia was as manager of a modest place of 300 acres belonging to a ninety-year-old doctor. My Mother came out to house-keep for me – the rest of the family were to follow if she liked it. Within six months, however, my Mother was on the verge of a nervous breakdown. Those six months of adventure and misadventure really topped everything; so, I returned with her to England. I made the best of it by falling violently in love, for the six weeks’ voyage, with some lovely, mysterious beauty who shared my Mother’s cabin.

In England by 1927 I felt that I was not destined for any orthodox agricultural success. In one way I was serious minded and prepared to put my agricultural training into practice but the antics of the Australian characters seemed to me as diverting as the antics of my fellow students had been. I do not know how it came about but I got feeling more capable of living and less capable of any specialised success. This made living at home with Father rather difficult, so in 1930 I set off for Canada.

I started off in Canada with two loves – the outer life of a farm worker and the inner life of a free thinker. After seeing the sights of Montreal, I took a train to Ontario and a Mr. Fulton who stood over six feet in his socks, had a virile looking beard and was, in his slow way, as tough as they come. He loved to plough in April when the soil would come up in half ton frozen chunks. When that was completed, he turned to his duties in the local graveyard, and we would dig graves furiously to accommodate the dead who had been waiting in their special house above ground all winter. He used to measure the graves with his own frame and more than once I found him six feet down, arms crossed – and asleep! Although in his late sixties, he chose the extremes of weather for the most exacting chores, and he was quite a sight when the lower half of his face became a solid mass of frozen tobacco juice. His family, however, had the comfortable habit during the winter months of keeping the outdoor toilet seat behind the stove in the kitchen.

Agriculturally speaking, my sojourn with the Fultons was perhaps the most satisfying of all my twelve years on farms. I was even able to use some of my fast-fading theoretical knowledge to improve their milk production; learning, incidentally, that the transference of knowledge from the lecture hall to the cow stall has its dangers. Canada is a great country but, in the corner where I chose to operate in the early thirties, I did find one or two places where cleanliness was too much trouble. The sometimes intense cold of the winter makes certain operations difficult while it also contains the bad smells of neglect: but there is a heavy price to pay for this in the Spring when a clean up may well be impossible and certainly expensive. One such place was run by a woman and her several daughters: the daughters fascinated me, but I resigned on religious grounds. They were “Holy Rollers” and held prayer meetings in the home every night. Reaseheath had not prepared me for that combination. For that matter, I had no preparation for the next item – a glass eye recently acquired my next farmer-boss. He could put it in, but he could not get it out and it hurt him at odd moments. When I had got the knack of it, this eye extraction dominated my days. I would be enjoying some bare foot ploughing when the call would come from the next field, and I would have to run for my boots to get over the stubble and perform the operation.

I’m afraid I changed jobs rather frequently about this time and to save expenses I hired out to a farmer within fifteen miles of Montreal. This farm was an acre wide and one hundred acres long but otherwise a sound and productive proposition. One incident showed up our lack of veterinary knowledge. I still don’t know what ailed the cow that could not rise from her lying down position. She seemed contented enough, chewing away at her cud. We decided to lift her – one at each corner, all together boys, slow but sure, up she came. The lady disposed of one cud and reached for another, with her legs still curled under her. We were getting a little short winded, but each held on to his 150 lbs. of cow. Bessie did not miss a chew but eventually turned her head and surveyed us. Then I caught the boss’s eye just when he was beginning to feel foolish and I’m afraid I giggled. I had just enough strength to lower my corner with the others and stagger off to do my laughing outside. It was a most stupid and exhausting performance, but it struck me as very funny.

While on this farm I met the girl who was to become my wife. Marriage virtually ended my agricultural career though we tried a three-month spell of farming just after the last war when I had come out of a war plant and jobs were hard to get. It was conclusively proved that my wife and large animals could not co-exist at such close quarters. Horses snorted down on top of her head, cows nosed her to one side and chickens became explosions of feathers under her feet. My employer was an ex-translantic pilot with his nerves all shot. He could not milk, would not learn and thought cows gave milk forever – “to hell with lactation periods and other scientific rot”.

We pulled out about 1946 and I got into newspaper work in Montreal where I stayed until coming to England in 1956. I have not found anything suitable here so we are contemplating a return to Canada though we would prefer to stay in England. My wife loves England and our three children have settled down very well.

From a cultural point of view this is not a very edifying recital but somehow my buoyancy and bounce seem to increase with the years. If this is any sort of success, I think I know where I found the beginning of it – in your own hallowed halls, labs, lecture rooms, dormitories and playing fields.